One Calls This Reading: First Thoughts on Michael Lentz's Schattenfroh

My initial impressions after finishing the book

A note for those curious to dive in: This excellent blog post helped me greatly with understanding the art references in the book. It was the most useful resource I found in English.

“That’s not a book. That’s a weapon.”

-The Barista at my local cafe, when he saw me pull Schattenfroh out of my backpack.

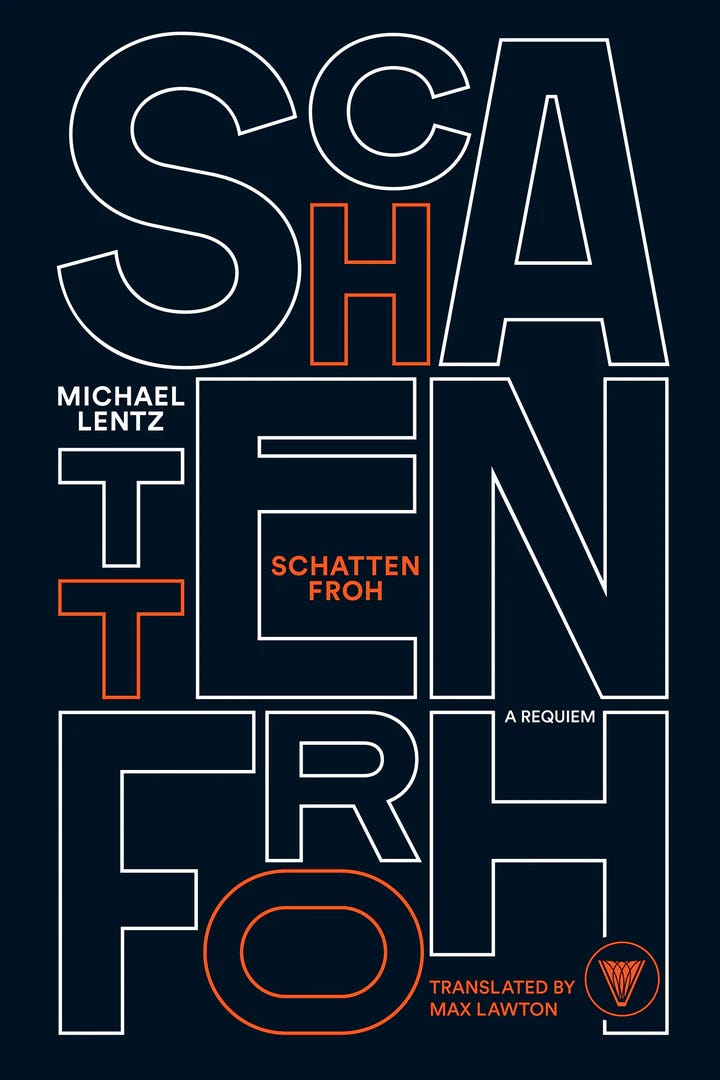

There were two things I did immediately after finishing the last page of Michael Lentz’s 1000 page mega-novel, Schattenfroh, whose English translation, by Max Lawton, was recently published:

I took several long, deep breaths in a row. To steady myself.

I shook my head back and forth a bit to help clear my vision, which was blurry.

I’ve spent most of the the last ~15 days working through the book, and while at first I found it to be a bit distant, somewhere around page 150, something shifted (or shifted within me). I started to better grasp not just the book’s massive Thomas Mann-esque block paragraphs, it’s medievalism-on-steroids use of esoteric symbols and allusions, its formidable and wily ekphrasis, the kooky typography, etc.…but more than that, I felt as though I was starting to pick up on one of the emotional hearts of the book (like some alien life form, Schattenfroh has more than one).

Lentz deploys all of this staggering, world-beating literary erudition in service of many goals. But chiefly, I think in Schattenfroh he’s trying to come to grips with and better understand who his own his father was, his relationship with his father, and to weave a massive, mytho-philsophical work that forces readers to acknowledge that the role our fathers play in our lives is larger, more profound, and more all-consuming than even modern psychology might be comfortable admitting (how very German of him). As Lentz himself writes, well into the novel’s final quarter:

My book is an absolute book, it has apocryphal parts and two centers, my book is one person as two — which are my father and me.”

Schattenfroh, page 823

All of that I get. But I wasn’t expecting all of that to be so fun.

For a mammoth work full of hyper-dense syntax, Schattenfroh is enlivened throughout by Lentz’s pedal-to-the-metal narration. The momentum in this book is unlike anything I’ve ever read before. Our narrator ‘Nobody’ (who might just be Lentz, or a proxy of him, or some parts of him, etc.) has what might be the best sense of ‘velocity’ I’ve ever encountered in a large novel. He keeps things moving along.

Even when we dive into byzantine cabalistic references, or brain-melting discourses on medieval theology, the intelligence at work here is simply too powerful, too ironic, too in command of the centuries of knowledge it brings to bear, to let things become bogged down, or inert. I have read plenty of novels of similar size and scope that got spun around and lost within their own, show-offy, bloat. That never once happened when I read Schattenfroh.

I have read plenty of novels of similar size and scope that got spun around and lost within their own, show-offy, bloat. That never once happened when I read Schattenfroh.

In fact, the book continued to pick-up steam the further I got into it, and the more fully I became embedded in its recursive, anagrammatic logics. Even when Lentz dives full-bore into autistically rendered technical logorrhea, or the minutia of German regional history. Even when he seems to jump down into what most novelists would consider foolish, bottomless pits of no return. He does so not to leap out of those pits again, but to blast down through their floors and into wild, subterranean spaces where history, family and theology merge into a primordial, shadowy stew we’ve all, somehow, avoided noticing.

There were at least ~15 times during my reading of Schattenfroh when I said, out-loud, “Oh my god.”, “is he…?”, “he can’t do that.” Every time I thought the book would collapse, exhausted, under its own weight or back itself into a corner it couldn’t extract itself from, Herr Lentz just kept on kept on muscling onward, casually fearless, and seeming to prove that all existing conventions of the novel are only there for him to shred, blend and bend into the beguiling, colossal form that his book takes.

Every time I thought the book would collapse, exhausted, under its own weight or back itself into a maze it couldn’t possibly extract itself from, Herr Lentz just kept on kept on blasting forward, casually fearless…

Like Gulliver in Lilliput, I found Schattenfroh managed to pull me in, not with a single moment or passage (though there are many killer sequences in here), but with a tiny series of brazen, weird stylistic harpoons whose collective power slowly sank in and yanked me deeper and deeper into the patterns and threads that Lentz assembles and reiterates. And which came to feel as familiar, as human, and as beautifully sad to me as any ‘plot point’ in any conventional novel I’ve ever read.

A work like this seems purpose-built to eschew any easy or totalizing summary, but there is one old latinate word which, for me, comes close to hitting on what I thought of the effects of the book, and the skills of its author:

magisterial: “of or befitting to a master or teacher or one qualified to speak with authority”

Schattenfroh reaches for the outer limits of literature and really, language itself. With fierce power, it handily lands in that strange, babbling zone occupied by writers like James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, William Burroughs, etc. Those oddballs whose books’ freakiness is matched only by their ambition to hammer words and sentences into brazen, new shapes. Like their works, Schattenfroh is proof that the modern novel, as an art-form, still has boundless space to grow. Provided we can provide it more light, more darkness, more of everything we ourselves are made of.

Schattenfroh is proof that the modern novel, as an art-form, still has boundless space to grow. Provided we can provide it more light, more darkness, more of everything we ourselves are made of.

And so, what I felt viscerally just after finishing Lentz’s book, and which caused me a sense of true vertigo that lingered for several minutes, was a sensation that the art critic Robert Hughes succinctly described, in the title of his famous work on the history of modern art:

Schattenfroh made me feel ‘The Shock Of The New.’

Have you read Rodrigo Fresán’s “Melvill”? Other than the length, this description reminds me a lot of it. It, too, is an apocryphal book with two centers, one Herman Melville, and the other his father.

Curious about this one, in large part because of Lawton's work with Sorokin. Can't imagine he'd spend this much time on an author who didn't have something interesting going on.