My first full month of being unemployed translated to my biggest month of reading, probably ever in my life. I finished 10 books in July, as well as completing the first draft of my first novel! My reading this past month once again spanned a wide gamut, but I ended consuming a bit more speculative fiction in July than what I usually do. With two exceptions I will discuss at the bottom, everything I read was worthwhile in July. And particularly I Who Have Never Known Men, which is a bona fide masterpiece on its own that transcends the hype.

The Traitor by Michael Cisco

My Second Cisco book, and both more conventional and darker than The Divinity Student, which I read last month. The Traitor is a haunted, cyclical first-person narration a la Thomas Bernhard or Samuel Beckett. We follow the recollections of a spirit healer, who befriends a completely doomed, totally fucked, soul eater (pretty much what is sounds like). Cisco’s control over the narrative is casually masterful, and his descriptions of the man’s discovery of his powers is just…brilliantly, casually horrifying. The narrative control here, the sense that we only see the tiniest fragment’s of the deeply sick relationship between these two men is brilliant. There is a bitterness and sense of violence, both visceral and social, in this that borders on the hypnotic. Cisco is an under-appreciated visionary.

The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch by Philip K. Dick

I haven’t read PKD in about ~12 years and picking this up in 2025 proved to me that he is still as queasily prophetic now as he was in the 1960s when this came out. Computerized therapists, an earth scorched by impossible temperatures, but above all…the titular Palmer Eldritch. A post-human 1 percenter obsessed with forcing the world to join him in a collective hallucination that promises limitless, dopamine-driven bliss…as long as he’s the one running the show. This is barely even a cipher for the narcissistic self-regard of America’s billionaire class in 2025, who will never be placated with any amount of fawning or fealty. PKD is often acclaimed for his spiritual/theological themes, but what impressed me the most here was his brilliant rendering of the psychosis of the ultra-wealthy; of how miserably non-human their lives and relations to the rest of us are.

The Fifth Head of Cerberus by Gene Wolfe

One of the greatest works of American fiction of the 1970s (a decade which produced no end of bangers) regardless of genre, style, etc. Wolfe’s second book weaves together a staggering narrative braid from three different tales about twin worlds whose native inhabitants have disappeared amidst subsequent waves of colonization, or so it seems. He creates a narrative puzzle box of signs and signals which resonate and reconfigure themselves with each tale, and which reward close, deep readings and re-readings. Wolfe layers questions about authenticity and fakeness, of who is an insider and who is an outsider, with a level of poise and literary filagree few writers possess. In a world where power and colonial conquest consistently work to muddle who ‘belongs’ and who does not…what happens to the people caught across the lines of those inclusions and exclusions? The world he writes about is a fantasy. It is also simply, our own.

Strange Houses by Uketsu

What an odd little thing this is! A j-horror murder-mystery composed of floor plans, timelines and diagrams as much as text. Uketsu weaves together these delicate, ominous little threads, turning the most mundane of domestic details into eerie premonitions of darkness, violence and family madness. Honestly, the book ends up going to some places that will test many western readers suspension of disbelief, but I found it delightfully weird and dark, in an intensely Japanese way, even if the finale left me rather cold. Regardless, this book is a masterful display of the power of small gestures and tiny hints. Of how the ambiance of evil can seep in from even the most quotidian details of the physical spaces around us. This is the very essence of horror.

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson

I’m embarrassed to admit it but I’de never read the granddaddy of all adventure novels prior to this. Any aspiring writer would benefit from spending the afternoon it takes to polish this off. Stevenson, writing from the early 1880s victorian era is simply unmatched at his ability to orchestrate and push forward action as a young man discovers a mysterious map and encounters the legendary Long John Silver. Who ironically, is almost the archetype of what we call the American character today: self-serving, endlessly greedy, and nihilistically alone. Give a copy of this to every dullard out there who writes books about sad people who sit in sad cafes having their sad lattes and croissants. Stevenson, along with Alexandre Dumas, shows how to MAKE. THINGS. HAPPEN. on the page like no one else.

Tropisms by Nathalie Sarraute, trans. by Maria Jolas

The tiny little book that (arguably) launched every big ‘ism’ in 20th century fiction from 1940 onward. Sarraute’s little vignettes aim to describe those interstitial spaces between action, thought, and character: the odd little affects that actually compose most of the moments of our reality. The DNA of so much we love winds its way back to this collection of shadowy conceits. Everyone from Don Delillo, Thomas Pynchon, Lydia Davis, Maguirte Duras, Thomas Bernhard, Gabriel-Garcia Marquez, Julio Cortazar, Elana Ferrante, Jonathan Franzen, David Foster-Wallace, Rachel Cusk, Joan Didion etc., as well as the various movements within modernism / post-modernism / magical realism / fabulism/ maximalism/whatever-ism…they all have their foundations in the minuscule, fragmented moments Sarraute conjures here.

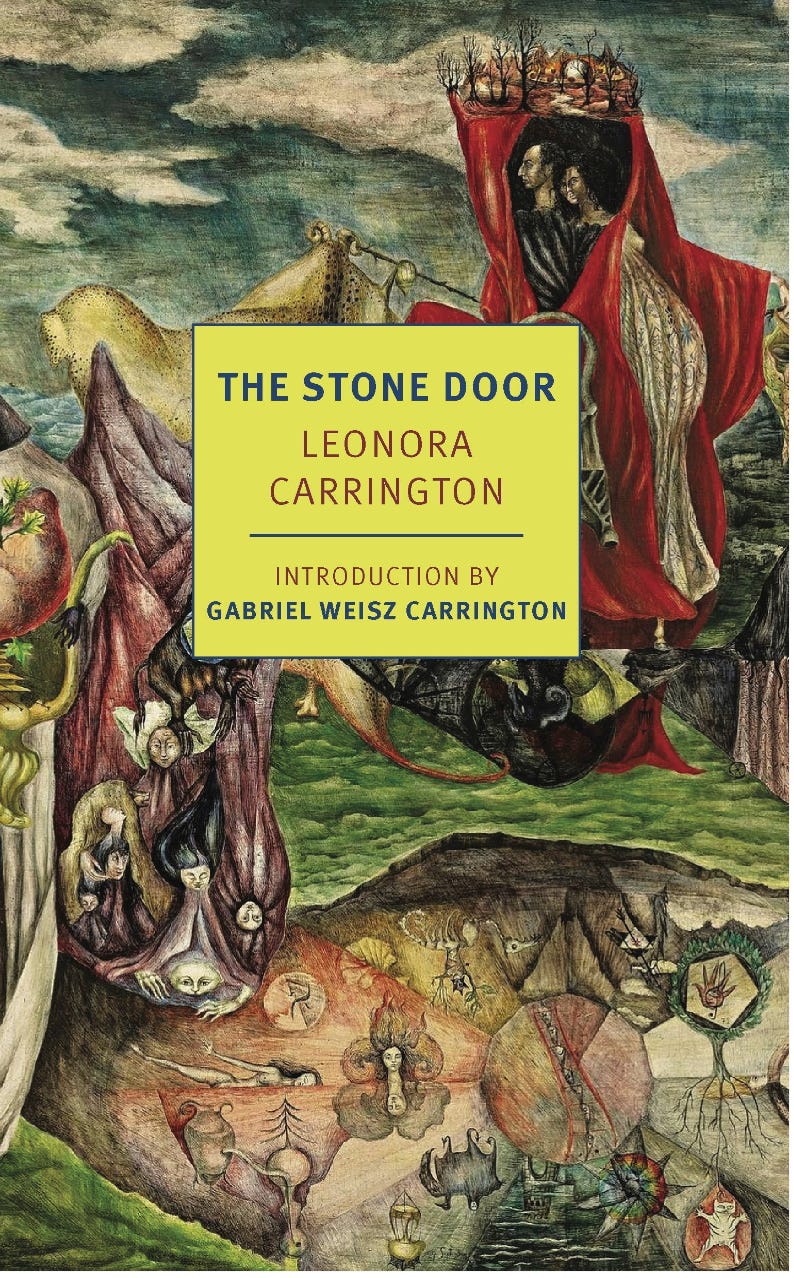

The Stone Door by Leonora Carrington

An ecstatic, intensely personal mythology, dripping with arcane and mystical symbolsim from an under-appreciated surrealist master. The Stone Door trades off on multiple layers of dream visions and dream logic, as Carrington works to unite herself, psychically, cosmically, etc with the spirit of her husband, the Hungarian artist Chiki Weisz. The structure of this is delirious, but also cunningly crafted, as symbols and icons bleed into each other across different layers of dream reality. Don’t be fooled, this is a staggeringly well designed little narrative.

I Who have Never Known Men by Jacqueline Harpman trans. by Ros Schwatz

The realist of things, and the rarest: a work of fiction that is far greater than even the hype which currently surrounds it. This is a humbling tale of a person who does not lose their humanity, but who never even had the chance to claim it. Harpman takes us inside the mind of a young woman raised in a bizarre, sick captivity whose only socialized and acculturation comes second hand, from the older-equally bewildered women around her. The book is sad, beyond even what tragedy is capable of, and yet, powerfully, movingly affirming. Even when faced with a future that is as much an oblivion as the past…even here, we see the power of the mind and the heart to make sense of the world, and therefore, to make sense of oneself, in whatever limited capacity one can. I was brought to tears at least four different times when reading this. It is like Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus, as a novel. Quite simply a great work of literary art. I recommend this book unconditionally.

The two stinkers I read in July

Alaric the Goth By Douglas Boin

A well-intentioned work of history that, alas, simply does not have the resources to bring real insight or rigor into an often-overlooked ancient life. We have precious few primary resources on Aleric himself (the guy who sacked Rome), and so Boin is forced to engage in what almost feels like historical-fiction-novel levels of conjecture on the man, his precise motives, what he was feeling from the few meagre records of him that survived, etc. Even as a wide-ranging portrait of the late Roman Empire, and how its exclusionary nationalism went hand in hand with christian militancy (sound familiar?), it still feels scattered, unfocused and simply falls short of any kind of standard for how to write good history.

The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley

Pure trash. Everything I detest in ‘big publishing’ literary fiction in a single book. Bad writing, dullard characters, hyper-uneven plotting, social commentary that is shoe-horned in in large, clunky chunks, a climax that tries to inject the specrte of climate catastrophe at the end to compensate for the fact that…nothing was really at stake for the past 300 pages or so…I could go on. This is 3 or 4 substantial drafts short of a proper finished novel, in my view. We read this for my book club, and most of us absolutely hated it. It was fun shitting on this book. Before anyone gets mad at me… the book has already been optioned for a film by the BBC, so don’t worry. Bradley is smiling all the way to the bank. She should use some of the payout to consider taking an ‘intro to writing’ class.

You make Wolfe, Saurraute, and Harpman sound awesome. I’m going to have to find these. I’m particularly interested in Saurraute, since I’m into visual metaphor/things not expressable in words. Sounds like her words have something for me. Also, it’s rewarding to hear you take out the trash! I get so tired of the circle jerk of bestsellers.

You will love tropisms. The kind of book you can sit in a cafe and read in one go. And definitely something worth revisiting.